|

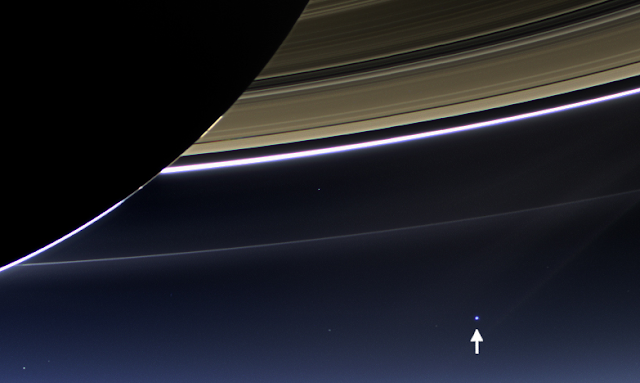

| Photo: Flicker/ by Lawrence OP |

"This disquiet

comes from within and not from without … if you do not change the interior man,

you will never do good. And you will everywhere be the same, unless you succeed

in being humble, obedient, devout, and mortified in your self-love. This is the

only change you should seek. I mean that you should try to change the interior

man and lead him back like a servant to God." Excerpt from Ignatius of Loyola’s letter to Bartolomeo Romano.

Today’s

Feast of St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556)—the founder of the Jesuit Order—is a good day to

consider what Catholic thought can and must bring to discussions of ecological

crises.

I was reminded of this at work yesterday while listening to a webinar on the relation between

sustainability and security—how the causes and impacts of ecological ills often

result from or lead to social unrest or military actions. It was something of a secular conversation about what the Church calls "human ecology." That is, just as nature has physical laws, it also has laws about being human and living in human communities. What the speakers were saying was that there is a link between these physical laws and their human counterparts—and that is exactly what Benedict XVI is saying in the quote at top.

The speakers raised concerns about how changing environmental and economic realities may cause social disturbances. For

instance: As the Arctic melts, who will control new shipping lanes and the

resources beneath them? As droughts intensify in economically stressed regions (as they already have),

who will control the dwindling sources of water? When worldwide demand for the

minerals needed for our electronics results in deadly conditions for miners (as it already has), how

long before civil unrest breaks out?

As

I listened to the presenters—very intelligent people who hold very impressive

positions at very influential organizations—it was clear that while they made

some good observations none of them could offer definitive insights about the human person or the common

good.

A

horrible moment came when someone asked what nations can do to control their populations.

The main speaker, an American researcher at a prestigious think tank, said that China’s

one-child policy “has worked pretty well.” She quickly admitted that there were

some "negative effects" with this policy, but she didn’t sound convinced that they outweighed what she saw as its benefits.

There

was much that I wanted to add. But my responses were rooted in my Catholic faith and, as I was on the state clock, my words would would not have been appreciated.

If

I did have the opportunity, I would have echoed the recent words of

Ghana’s Peter Cardinal Turkson, who spoke last week about ecology during World Youth Day. It

will take an “authentic ‘conversion of heart,’” the cardinal said, to tackle

the ecological issues of our age. These words echo those of Bl. John Paul II

and Benedict XVI; the latter once noted that to live sustainably, humanity must

align our “inner attitudes” with the laws of nature—human and otherwise—which ultimately

we can only do with the grace of God.

Here,

the spiritual writings and example of St. Ignatius of Loyola have much to teach

us. His words in the letter above are worthy of reflection not only in their original sense but also now in the modern context of human over-consumption. Elsewhere,

Ignatius pointed to what he called the “discernment of spirits.” The website

ignatianspirituality.com, a resource by Loyola Press, explains that term this

way:

Here,

the spiritual writings and example of St. Ignatius of Loyola have much to teach

us. His words in the letter above are worthy of reflection not only in their original sense but also now in the modern context of human over-consumption. Elsewhere,

Ignatius pointed to what he called the “discernment of spirits.” The website

ignatianspirituality.com, a resource by Loyola Press, explains that term this

way: Discernment of spirits is the interpretation of what St. Ignatius Loyola called the “motions of the soul.” These interior movements consist of thoughts, imaginings, emotions, inclinations, desires, feelings, repulsions, and attractions. Spiritual discernment of spirits involves becoming sensitive to these movements, reflecting on them, and understanding where they come from and where they lead us.

Elsewhere

it adds,

Ignatius believed that these interior movements were caused by “good spirits” and “evil spirits.” We want to follow the action of a good spirit and reject the action of an evil spirit. Discernment of spirits is a way to understand God’s will or desire for us in our life.

Talk of good and evil spirits may seem foreign to us. Psychology gives us other names for what Ignatius called good and evil spirits. Yet Ignatius’s language is useful because it recognizes the reality of evil. Evil is both greater than we are and part of who we are. Our hearts are divided between good and evil impulses. To call these “spirits” simply recognizes the spiritual dimension of this inner struggle.

After

a cursory review of Ignatian spirituality—which I first read about for an early post on Pope Francis—I am certain that such spiritual considerations could have added much to that webinar about sustainability and security. True

security comes not from raw human will but from our will aligned with God’s—our nature elevated by His grace.

Consider

for a moment the greed and gluttony that fuels so much ecological harm. And

then consider what St. Ignatius had to say about his concepts of “spiritual

desolation” and “spiritual desolation.”

Again,

according to Ignatianspirituality.com, spiritual desolation is

an experience of the soul in heavy darkness or turmoil. We are assaulted by all sorts of doubts, bombarded by temptations, and mired in self-preoccupations. We are excessively restless and anxious and feel cut off from others. Such feelings, in Ignatius’s words, “move one toward lack of faith and leave one without hope and without love.”

an experience of being so on fire with God’s love that we feel impelled to praise, love, and serve God and help others as best as we can. Spiritual consolation encourages and facilitates a deep sense of gratitude for God’s faithfulness, mercy, and companionship in our life. In consolation, we feel more alive and connected to others.

I am convinced that it will only be such spiritual exercises—and the growth and transformation that they offer—that, with the grace of God, will save

us from ourselves.

Government policies and laws can do much good when rightly ordered. But there is no guarantee that they will be rightly ordered and even when they are they can only take us so far, and not far enough.

Government policies and laws can do much good when rightly ordered. But there is no guarantee that they will be rightly ordered and even when they are they can only take us so far, and not far enough.

Catholic

ecologists cannot shy away from this truth: Our salvation comes only from

Christ. The sooner this good news is shared and lived the sooner we can tackle

the environmental crises that are here now and that are coming our way.

And

so on this feast day, let us pray that the whole world can and will listen to voices

like those of St. Ignatius, Cardinal Turkson, Bl. John Paul II, Benedict XVI,

Pope Francis, and especially Christ—for He is the only way, truth, and life that

can make our lives sustainable, secure, and eternal.